Your best friend is a gay Mormon and you saw the pain that she went through to acknowledge her sexuality and navigate her role in the church and her family. Or perhaps you saw the protests in Ferguson and wondered what if you weren’t white and your own kid was in that situation. Or maybe you saw how your sister worked and sacrificed at her job only to be paid less and consistently passed over for promotions.

And you want to do something, anything, to help.

Awesome. You are taking the first steps towards being an activist. I know the word “activist” has a negative connotation, especially in the LDS community, but just look at the word, itself. “Activist” simply means “one who acts”. If you do something to help, if you act, you’re an activist. And that’s something to be proud of.

Now, it can be tricky when you are an activist trying to help a group for which you personally aren’t a member. For these people, the term “ally” is often used. But being an ally is no easy task. It may seem like you are constantly saying and doing the wrong thing and that probably is because you are constantly saying and doing the wrong thing. You’ll probably find this extremely hard to deal with. After all, you are in this to help people, not hurt them more. Sometimes it may seem that you are doing more harm than good and it would be better if you stopped trying to “help” at all. But don’t give up! There are some things you can do to avoid those very common mistakes among allies. But first, we have to talk about a few foundational things.

Privilege Trigger Warning: I’m about to talk about privilege

People in positions of privilege often get really upset when it’s implied that they are, well, in a position of privilege. They think the assumption is being made that they haven’t worked for the things that they have in life. For them, privilege means that there are people out there that think that because they are white and male, for example, that their life has been easy and that everything has been handed to them. But this is not what privilege really means. Privilege means that our society gives more advantage to some groups than other groups. That’s pretty much it. You still have to work hard and take advantage of opportunities in life, but there are some groups for whom those opportunities are far fewer because it’s much less likely that people will give them the benefit of the doubt, no matter how hard they work. Some succeed, of course, but the odds are not in their favor.

A very simple example of this comes from my elementary school. My parents and family were very well respected. We weren’t rich, but we were seen as honest, good people. Which was true in almost every case. Very early in my life, I got the reputation as a “good kid”. One day in elementary school, when I was walking back from the cafeteria with a friend, there was a really, really annoying kid from a younger grade that was provoking me. I had had enough of it so I started throwing rocks at him. A little later, I was pulled out of my class by this kid’s teacher who asked me if I had thrown rocks at the kid. I admitted that I did, but that he was calling me names (mind you, even at the time I wasn’t deeply hurt by what the kid was saying, just annoyed).

“I thought so,” she said, “I told him Clint wouldn’t have done that unless he had had a good reason,” and I was allowed back to my classroom and he was punished for provoking me. Let’s review: a younger kid was being annoying, I responded much more violently than was reasonable, and he was punished while I faced no consequences. You see, I was a “good kid” and “good kids” didn’t do bad things so if it was done by a “good kid”, it must have really been a good thing. He was a “bad kid” who did “bad things”. My reputation as a “good kid” meant that even though what I did was worse, objectively, what he did was deemed worse because he was a “bad kid”. And that’s kind of how privilege works. Some people are treated better than others, not just because of their actions, but because of the assumptions make about the generalizations of the people involved.

Fast forward to college. I had maintained my reputation as a “good kid” in college mostly by virtue doing things a “good kid” would do. I wasn’t using my reputation to my advantage or being false, it was simply how I interacted with the world. We were allowed to use the editing suite for any projects we wanted, not just school projects, as long as they weren’t commercial. A friend was working on a short film and was editing the movie with some other friends that included someone that wasn’t currently a student. I was in the editing suite cutting my own project, but I was part of discussions about their project as they worked collaboratively.

Later, I was pulled aside by a professor who asked if I had been involved in my friend’s short film. I said that, no, I was not involved in the project. He was angry that a non-student had been allowed in the editing suite, which was against school policy. There were tens of thousands of dollars of equipment in the suite so it wasn’t an unreasonable policy to only allow students in who unlocked the door with their student ID (which maintained an access log). Later I became angry. Everyone on that project were “good kids” and nothing bad was going to happen. I felt the assumption that these kids would steal anything from the room to be deeply disrespectful.

Basically, I had had someone check our privilege. It didn’t matter that they were “good kids”. They broke a rule and being “good kids” shouldn’t have absolved them from the consequences of their actions (as minor as those consequences ended up being). “Privilege” doesn’t demand to be treated equally, “privilege” demands to be treated better and gets very angry when it is treated the same as everyone else.

What does this have to do with being an ally?

Most Frustrations Allies Express Stem From Privilege

Saying that privilege is the root of most of the problems that new allies face sounds like an oversimplification, but when you look at the most common complaints and frustrations that new allies have, this can become more apparent. Often times frustration comes from pushback at saying the “wrong thing”. You mean well, but people seem to always jump all over you every time you say something. Even if they do so in a polite way, it can be frustrating to face such frequent resistance. There are some frequently uttered statements from new allies that will face pushback from most minority communities.

“It feels like my contributions aren’t really valued.”

Perhaps you are being unfairly treated, but it’s also likely that it’s not so much that your contributions aren’t valued, it’s that they aren’t given extra value. This probably feels untrue to the heartfelt ally (you are there because you value equality, after all), but often times we expect people who are “lower” than us to defer to us and our opinions. This happens often when men enter feminist communities and are not used to being dismissed, shut down, or criticized by women. They aren’t trying to be sexist, of course, but many, many women in the U.S. are raised to defer to men in conversations and we all get used to it happening that way, even if it seems like we are having an equally weighted conversation. In feminist conversations, those dynamics are usually not adhered to and to the man used to them, it seems disrespectful and downright rude, but it’s because we’re experiencing for the first time what it is like to be a woman on the other side of our conversations. It’s not like what you have to say isn’t valued, it’s just that usually you experience value inflation and you’re now experiencing a more equitable dialog.

“It shouldn’t be so hard to help.”

This is related to the first statement, but more easily illustrates the arrogance of privilege. This statement implies that the solution is simple and if people would just let you help, you could make a real difference. The reality is activism is very, very hard. There are reasons why sexism, racism, homophobia, etc. exist in the world still. If they were easy to solve, they would have been solved already. You may have some good ideas as a new ally, but it’s more likely your ideas aren’t taking into account a lot of considerations that you aren’t aware of or perhaps ignore a long history of social dynamics that prevent your idea from ever working and so your thoughts and ideas may seem to be constantly resisted. That’s not saying that you don’t have something to offer and that your ideas don’t have some value, but trying to change the hearts and minds has never been nor will ever be easy.

“I’m so tired of hearing about x.”

You are probably saying this because you have been so emotionally enveloped in x that you are simply exhausted. You are probably saying this because you want to show your friends in the minority community just how much x has meant to you. The problem is that you are complaining about something that isn’t actually happening to you. It’s affecting you, of course, but it’s affecting you from a position of privilege because, in reality, it doesn’t affect or represent your day to day experience. But for those in the minority community, if every much does, and hearing you say that you are tired of it may be met with exasperation because, well, they are the ones to whom this actually is affecting. Sure, you may be emotionally drained from the week-long outrage of following stories about Ferguson, MO, but you know who is more tired than you? Black people, for whom it was a much more direct representation of their daily life and hearing you as a white person complain about it won’t likely garner much sympathy.

“I’m an x, so I know what it’s like to face discrimination.”

This may seem unrelated to privilege because it comes from a place of discrimination. While there are common themes in discrimination and prejudice, but the differences of situation between minority groups are significant and this attitude can actually incubate a lot of ugly privilege even in minority communities. For example, the string of transphobia that you sometimes find in the gay male community or the homophobia that exists in corners of the black civil rights movement. The thing with privilege is that there are different kinds and you can be privileged in one respect but not privileged in another, such as the case of a white, middle-class woman or a white middle-class gay man. (If you are a poor black trans-woman, well, things are pretty stacked against you.)

“I just focus on loving each other.” or “We should be treating each other with respect.” or “I don’t discuss politics; I focus on people.”

This is often employed by people who want to engage with the minority community, but don’t feel comfortable with certain political assertions made by the group. Everyone chooses their level of engagement, of course, and not everyone in minority communities agrees with the nuance of politics, but there are usually some core tenants that most people in the community share. An ally who expresses the above is often uncertain or uncomfortable with those political assertions. This also is rooted in the privilege of being uncertain. A man raising a child with his same-sex partner has less of the luxury of uncertainty as the rights afforded by marriage make a real difference in his life.

Such statement above are not always overtly useful as they don’t always indicate the level of commitment to community goals or even basic concepts. There are plenty of people who think gays are should be “treated equally” by restricting them to marriages with opposite-sex partners. There are some who express their “respect” for gays by not being distracted by their homosexual afflictions and respecting the straight person they are “underneath”. You should always be authentic, of course, but selective engagement and acceptance of group goals will usually be met with selective engagement and acceptance in return.

That may sound a little harsh, but consider the hypothetical situation where there is a clamor to remove the tax-exempt status of the LDS church (because, let’s be real, probably anyone reading this is or was LDS). You have two protestant friends, one who vocally disagrees with this effort and speaks out defending the LDS church’s right to exist as a legally-recognized church and another who whenever is asked insists the focus should be on “loving each other and treating each other with respect.” Now, it’s possible that you’d just accept that as it is, but it’s also possible you’d think, “um…so what does that mean?” Any feelings toward the two people are likely to be somewhat different.

Check your privilege at the door

“Check your privilege” is sometimes used to shut down someone who has an opinion about a group about which they aren’t a member. More often, though, this is just the perception of the person being “checked”. What is often more the case is that someone’s privileges are causing them to make uninformed statements and that they should examine their statements from the perspective of the group about which they are speaking. Self-awareness is not an easy goal. We all mess it up sometimes, but there are some things we can do as an ally that will help us to avoid saying or doing the wrong thing.

Be sure you know what an ally is

Some people say that they are an “ally” when they really mean “friend”. You can be a friend to someone or a group without participating directly in their goals. An ally, however, means that there is an element of providing resources or direct support. Friend can be a passive thing. Ally is a title of action. Assuming the title of “ally” without actually speaking up for, providing material assistance, or some other form of active support will likely be met with resistance.

Educate yourself and allow yourself to be educated

One of the biggest problem with allies in activist groups is the ally assuming that they understand the politics and social dynamics of the issue and group so they speak confidently and lovingly as they say things that horribly offend the group. This is almost always accidental, but minority groups face ignorance in their daily lives and want to keep as little of it in their groups as possible. The best way to prevent thesis to learn as much as you can about the topic, from the group and on your own. Activist groups will be able to tell almost instantly who has and hasn’t informed themselves of the issues surrounding their cause and they will have varying degrees of patience with educating new members. Don’t assume it is their responsibility to educate you. And don’t take the attitude that they should spend more time with you because “they need all the help they can get”. Ignorance takes time and energy to correct so if they are spending much of their time informing you, you are a drain on resources rather than a help. When they do take the time to correct or inform you, listen. If you have sincere questions, ask, but do so with the intent of learning.

Don’t complain about your problems to the group

Being an ally is hard. I haven’t even talked about the consequences of being an ally from the perspective of the ally. The ally may face rejection and hostility from their own groups. They may make all sorts of financial, social, and emotional sacrifices. Then there is the energy of dealing with the politics and in-fighting of the group itself. There is also the real emotional toll that comes from empathy as they hear and help alleviate the pain that comes from the group to which they have allied themselves. The place to complain about this, however, is not the group itself.

This isn’t to belittle the sacrifices that ally makes, but rather to minimize saying the “wrong thing” by choosing who that thing is said to.

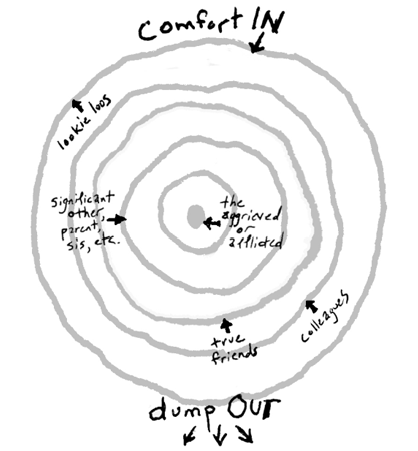

The “Silk ring” theory is an informal guide for complaining based on the idea that you should provide “comfort in” and negative emotions should be “dumped out.” The person in the middle of the ring is the one experiencing the “bad thing”, the first rung out is a the person closest such as a spouse or parent. The next ring is close friends and going out and out as the level of closeness decreases. You can complain about the “bad thing” but you should only do so to someone on your ring or further out; you should never complain to someone in a closer ring.

Applying this concept to the ally, the ally should be allowed to express the difficulties that they face as an ally, but they should do so to other allies or those further away from the trauma, never to people closer to the trauma. Doing so will avoid those situations where an male ally exhaustedly complains about trying to explain the problems that women face to a friend to a woman herself who is thinking the whole time, “I’m so sorry that was hard for you, try living it every day of your life.” That’s not saying that he can’t express his frustration, just that he should be conscious of who he’s complaining to.

This isn’t about you

In some ways it is about you. You have feelings of injustice and have experienced your own pain, but taking the Silk ring into account, for the purposes of the group, you are there to help and if you aren’t helping, you’re pulling resources. If you need help resolving your feelings around an issue, some questions to the group are certainly warranted, but their primary goal isn’t to support you. You are there to support them. This sounds cold, but remember that even though the activists groups are at the center of the Silk ring, allies are at the center of their own, different Silk ring and can (and should) help lift each other up and support each other in their ally-ship.

You can make a difference, really

Now this has been an extremely long post where it sounds like I basically call allies worthless and that they shouldn’t even bother. But the reality is that allies are desperately needed in every minority advocacy issue and that a lot of good can be done that only allies can do. For example: Mormons Building Bridges. MBB is an ally group for the gay community and in 2012 marched 300 people in Sunday dress in the Salt Lake City Pride Parade. Now, MBB isn’t perfect. They occasional say the “wrong thing” and don’t go as far to provide certain support that many in the gay community wish they would. But as I watched MBB march in the parade and saw members of the group breaking away so they could hug tearful gay people watching on the sidewalk, I saw the power of the ally. They can go places that we can’t go and can do things that we can’t do. We need people who are willing to stand where they wouldn’t be otherwise, stretch out a hand, and say, “How can I help?”

![[REC]](wp-content/uploads/2013/10/rec.jpg)